It’s a bit of a royal post today as many of the most memorable events of 20 June involve Kings, Queens, Would be Kings and others who ended up getting rid of a king and queen and lots of their chums.

In 1685 the Duke of Monmouth, bastard son of King Charles II, got sick of his uncle James II wanting to make England a Catholic country again and invaded the west country in an attempt to overthrow James. He is said to have undergone a coronation in Taunton on 20 June. James sent a royal army against him. Monmouth was defeated at the Battle of Sedgemoor near Bridgwater Somerset where I used to live. The battlefield is still there and worth a visit.

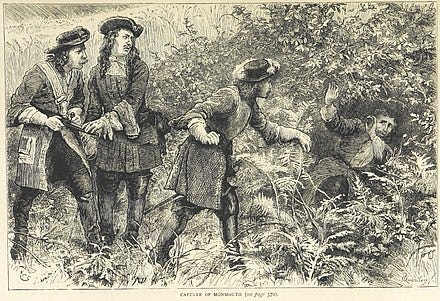

‘Found you!’ The capture of the Duke of Monmouth.

After the battle, the retribution was fierce, Monmouth was captured and executed. Knowing the executioner had a reputation as a bungler, he asked him to cut off his head with one blow. In the event it took five or six and Monmouth is said to have risen from the block with a look of reproach.

Judge Jeffreys was sent to Taunton and sentenced 170 people to death at the Bloody Assizes. His timing was bad, three years later James was deposed and Monmouth’s cousin Mary became queen with her husband, William of Orange as king.

Some legends say that James did not wish to cut off the head of his hothead nephew so he bundled him off to France where he was incarcerated for life as The Man in the Iron Mask.

A century and a half later the people of Somerset claimed that whenever Queen Victoria went through Bridgwater on a train she ordered the blinds to be closed so she did not have to look at the descendants of the treacherous inhabitants who had supported Monmouth.

‘We are not amused by the people of Bridgwater.’

Whether that’s true or not, we do know that she became Queen of England on this day in 1837.

Today, however, I’m going to concentrate on a different king, Louis XVI of France and the revolution of 1789. Because this day in history saw two seminal events in that momentous time.

King Louis XVI as a young man.

The second was in 1791. Louis was under house arrest at that time, and many thought that as a ‘good king’ he supported the people and would accept a role as constitutional monarch like King George III of England. He was perhaps the most liberal of all the kings of France so things may have turned out that way.

However, Louis was not that clever a politician nor much of a realist. He believed that the French people adored him, came to think that he had made too many compromises and found it increasingly difficult to navigate the tempestuous waters of the revolution. His advisors prompted him to try to escape and he fled north which suggested he was going to join France’s enemies. He also left a 25-page manifesto on his bed, careless man, which said that he was no longer willing to cooperate with the revolutionaries. Whoops.

He nearly made it to the border but was found because someone recognised him from his image on a bank note. Money talks. In Louis’ case with gallows humour.

He and his family were hauled back to Paris where a series of mishaps, most not by himself but by his friends, led to the inevitable. On 21 January 1793, Louis XVI was beheaded by guillotine on the Place de la Révolution. His wife, Marie Antoinette, was executed on 16 October. He went to his death in a rather nice coach. She was taken in a cart, enduring missiles and curses from the populace.

So where did this all begin? There’s a good case for saying that it started on 20 June 1789 in a tennis court.

But, naturally, the root causes stretched back decades before. France had once been the wealthiest and most powerful nation in Europe but a series of problems led to financial, social and political crises in the 1780s. The wealthy elite failed to notice the gathering tempest and resisted all demands for change. When will the rich ever learn?

Economic recession, failed harvests, unemployment and hunger became endemic and the corrupt tax system made things worse. In an attempt to solve the problems Louis and his advisers called a meeting of the Estates-General in January 1789. This was a general assembly meant to represent the three estates, the clergy (the First Estate), the nobility (the Second Estate) and the commoners (the Third Estate). It had last met in 1614.

There were 100,000 clergy and they were allocated 303 delegates, the 400,000 nobles had 282 delegates and the 28 million commoners had 289. You’d have thought they’d be grateful to have more delegates than the nobles but strange as it might seem to the wealthy, they were not.

It was assumed that the clergy and nobility would support the Crown and the commoners would always be out-voted. But the pesky commoners cottoned on to this and agitated for change. In the end the king doubled the number of their delegates to 578. Naturally, despite the name commoners, ordinary working men were not allowed to even vote to choose their delegates. And women were definitely not included. A bad decision - women were to prove some of the most influential in subsequent events.

Many of the clergy were poor parish priests and, to the king’s surprise, often voted with the Third Estate. Nobles did not have to be elected to the Second Estate but a number chose to be elected to the Third Estate and were to prove vocal in support of reform.

But Louis had a cunning plan. He decreed that each estate was to vote separately and the decision of their delegates would count as just one vote. So despite having more delegates the Third Estate effectively had only one vote, the same as the First and Second Estates. Talk about a con.

The Third Estate carrying the First and Second.

The Third Estate insisted on one delegate, one vote. The king refused and dissolved the Assembly.

Not only that, he ordered that the hall they had met in be locked so that proceedings would not continue. Another foolish move. Angry and undeterred, the Third Estate trooped off to find somewhere big enough to meet.

Luckily they heard some toff crying, ‘I say chaps, anyone for tennis?’

They marched to the Tennis Court and pledged not to disband until they had changed the constitution of France. This decision has been quaintly named the Tennis Court Oath.

The Tennis Court Oath

The king tried to keep the old system of voting in the separate orders but the Commoners held to the Tennis Court Oath and he was forced to acquiesce. A new National Assembly was created with each delegate having one vote. Game, set and match.

But he also assembled troops to surround the delegates. This outraged the people of Paris who were beginning to wake up to their ferocious, world-changing power.

The king’s days were numbered.