Unless they are writing about real people, as historical writers often do, authors have to invent names for their characters. Some find this easy; others agonise over it.

John Bunyan’s 1678 allegory, The Pilgrims Progress, made very clear how the reader was supposed to view the characters. They include: Christian, Obstinate, Pliable, Mr Wordly Wiseman, the beautiful maids Prudence and Discretion, the temptress Madam Wanton, Mr Sagacity, and Mrs Inconsiderate, Giant Despair and his wife Giantess Diffidence who was cruel and violent so not the slightest bit diffident. They’re like the Cuprinol advert – they do what it says on the box.

Although Henry Fielding named one of his characters Squire Allworthy most authors since have tended to choose names which don’t attempt to personify the individual character. That doesn’t mean they didn’t struggle for the best names.

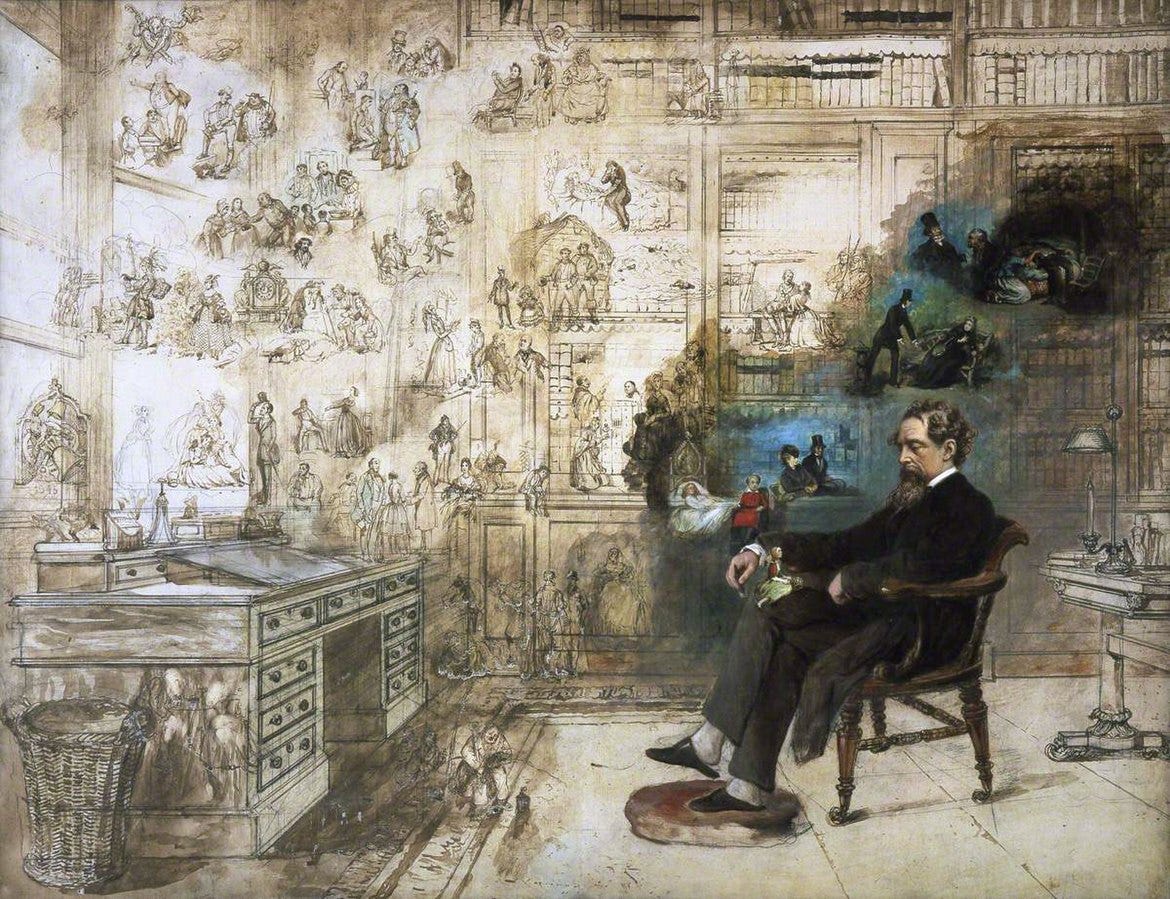

Dickens, in particular, took great pains with his names, which is all the more remarkable as he invented so many characters.

Dickens’ Dream. Robert W. Buss

His early novels occasionally harked back to earlier practice but more elliptically. In his second novel, Oliver Twist he gives us the magistrate Mr Fang, the cruel undertaker Sowerberry and the bumptious Mr Bumble who named orphans at the workhouse in alphabetical order, the young Master Twist’s predecessor being given the name Swubble.

In later books Dickens gives us the benevolent Cheeryble brothers, the bird lover and flighty Miss Flite and the cruel Mr Murdstone. There have been tales that Dickens prowled around graveyards to find names for his characters but I’ve found no evidence for this. In any case, why would the most imaginative of writers need to stoop to reading the names on tombstones when he could search his own mind?

But despite his great gifts he sometimes had trouble naming even his protagonists. Before settling on Martin Chuzzlewit, the young man was called Sweezleback, Sweezlewag, Chuzzletoe, Chubblewig and Chuzzlewig. His favourite character, the one based on himself was variously named Trotfield, Trotbury, Copperboy, Copperstone before he finally settled on David Copperfield.

I take similar pains with my characters. One thing I’m keen on is to have every character’s name begin with different letters. I think it helps to avoid confusion in the reader. This can take ages to keep to. Another problem I have in my Saxon and Viking tales is that the names are hard to spell and read.

In my new novel I decided early on that my faerie family would bear natural names. Hazel, Laurel and Fern are the females although they started as Cherry, Rose and Daisy, The males are called Robin and Merlin (at least so far.) Their surname proved more difficult. At first it was Goodfellow, from the alternative name of Puck in A Midsummer Night’s Dream. Then, thinking this too obvious it became Hobbes, Hobson, Good then Fellows, before I purloined the surname of the organist Earnest Japes.

The choirmaster Clarence Makepiece came very easily but his wife was called Lydia and Sarah before I settled on Emily. Their children were easier, Victoria after the queen, Elizabeth after the Tudor queen and Sybil because she can see things others can’t. I soon tired of Barbara and then remembered that parents sometimes name a girl child after their father so she became Clarabelle. I’ve gone through the draft in writing this post and find there are hardly any characters who haven’t suffered the indignity of a name change. Thankfully, changing names is easy on Scrivener.

A particular problem I have is naming books. My wife Janine and I would spend days trying to come up with the best title. I can’t recall the first titles I came up with for this book, lost of talk of boundaries and the odd poetic quote I seem to recall. But Hinterland quickly made itself known and I’m happy with this. At least for the present.

As is often the case, I’ve named some of my new characters after friends. They’re never villains although I occasionally find myself having to defend their actions to the person they’re named after.