This week, on 15 January 2001, Wikipedia was launched. The first recorded words are: "This is the new WikiPedia!" although Jimmy Wales, the founder (or co-founder) says that the first words, soon deleted, were “Hello World!” I think it’s entirely appropriate that there should be multiple versions of the first words and that Wikipedia started in the first month of the new millennium.

I’m a great exponent of Wikipedia although I use it in several ways. It’s my first resource for most things I’m looking into. Sometimes, I’m content with reading just the article.

The second way I use it is more rigorous. I bear in mind the potential weaknesses of this huge harvest of knowledge produced prodigiously quickly by volunteers and without peer review. In this case I read the article and then delve further to check other viewpoints and opinions. One of the problems of Wikipedia’s success, however, is that sometimes the sites I use to double-check an entry say exactly the same as the Wikipedia article. I’m never sure which is the original and which the copy.

But researching areas I’m familiar with, I find that most of the time Wikipedia is pretty accurate and without bias. (Unless, of course, I’m inaccurate and full of bias.) And I think it’s getting better all the time.

I am, incidentally, endlessly impressed at how quickly Wikipedia responds to current events. If someone dies, is involved in a scandal, is sacked or promoted, it appears on the relevant Wikipedia page quicker than on most other outlets.

The other thing to bear in mind is that encyclopaedias have always been prone to human error and prejudice. They are, after all, written by humans. And just because the human happens to be an academic doesn’t necessarily guarantee they are more knowledgeable or trustworthy than a volunteer. To illustrate the point, as a teenager I used to go the town library to delve into the Encyclopædia Britannica. I naturally assumed from its title that it was British but since 1911, it’s been American owned. (By the way all this information comes from – mea culpa – Wikipedia.)

The concept of seeking to collect all human knowledge goes back over two thousand years to the rival libraries of Alexandria and Pergamum, perhaps even longer in different parts of the world. Certainly, the first recorded library was in the Sumerian city of Uruk a thousand years before that. Perhaps even earlier, some wise woman of a stone-age tribe stored all existing human knowledge in her own mind.

The concept of using volunteers also has a venerable history. Richard Chenevix Trench, Herbert Coleridge, and Frederick Furnivall came up with the idea of the Oxford English Dictionary in 1857. They soon realised that it was beyond the powers of any one person to complete and would require a huge team of people, many of them amateurs.

The first edition was completed in April 1928, 70 years after it was first conceived. It was originally planned to be in four volumes with 6,400 pages but it ended up as ten volumes containing over 250,000 main entries and almost 2 million quotations. The Second Edition of the OED was published in 1989 and consisted of 22,000 pages in twenty volumes. It is now available online. You can buy a subscription or, if your public library subscribes, use that.

I owe much of my education to encyclopaedias and was an avid reader of Look and Learn. I was thrilled by its wonderful artwork and great articles.

My father was a great believer in part-works. One called Knowledge was based on an earlier Italian magazine called Conoscere. Dad bought it from the first issue in January 1961. I lived in a very smoggy London and suffered from chronic Bronchitis which meant I missed a lot of school. (Which was a delight for me as I hated all my schools until I was eleven). So Knowledge was my foremost educator.

It ranged across every field of western knowledge and the illustrations were superb. All these years later I can still visualise some of the pictures. It appealed to my butterfly brain and I hoovered up a universe of information. Dad gave me all 18 volumes and I kept them for years and regret that I eventually threw them out because of lack of space. Hey, I wonder if it’s been digitalised?

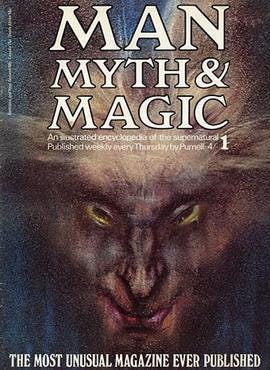

My father bought other part-works, one on art and one on the human body plus others I can no longer remember. I later bought Man, Myth and Magic, or as my mother once called it, Magic, Meths and Somewhats. It was probably an accurate description.

Man, Myth and Magic was an encyclopedia of the supernatural, mythology, religion and magic and introduced me to things like witches, elves, divination and alchemy. Just the thing for a graduate of Knowledge. Like with other part-works, the editorial board was extremely distinguished.

So Wikipedia stands in a long and noble tradition for me. Long may it continue.

What factual books have been most influential for you? Please leave us all a comment below.

I find Wikipedia a great ehlp in the first instances and I often read forward through the references which is a Godsend.

Like you, I was a Britannica child and if I recall, there was also a child's general encyclopedia that I was given. Dad had many non-fiction books in his library with illustrations and black and white photos which were helpful with school projects and homework. I also had a small and simple equine encyclopedia, being horse-mad - RS Summerhayes Book of Horses and Ponies.

Beginning my writing life with fantasy provided me with many reference books on myth and legend but the most outstanding has been Carol Rose's Encyclopedia of the Little People - Spirits, Faeries, Gnomes and Goblins. It can be a terrifying read!

But often, into my mind will pop a quarto-sized book with an orange cover which was a child's encyclopedia of myth and legend. I can't remember its title and have googled a million versions to try and locate it through secondhand bookshops. It was wonderful, both with illustration and story telling. I was probably 7-11 when it had its impact.