I started writing my new novel on 26 February. I often say that it takes as long for me to make a book as for a woman to make a baby. I’ve just counted up - it’s been nine months.

The last month has involved me in editing. I decided to ask one of my friends to do the developmental edit. We’ve been in a writing group for - yikes - over twenty years and she has always impressed me by her ability to get to the heart of a piece of writing and offer wise and incisive advice. She agreed to do my edit and she gave me more help than I could have imagined.

I’ve now sieved the novel through my software SmartEdit. It finds extra spaces, spelling mistakes, how often phrases are repeated (I’m glad to see that I’ve reduced my use of deep breaths and nodding heads) and - my favourite - risque words.

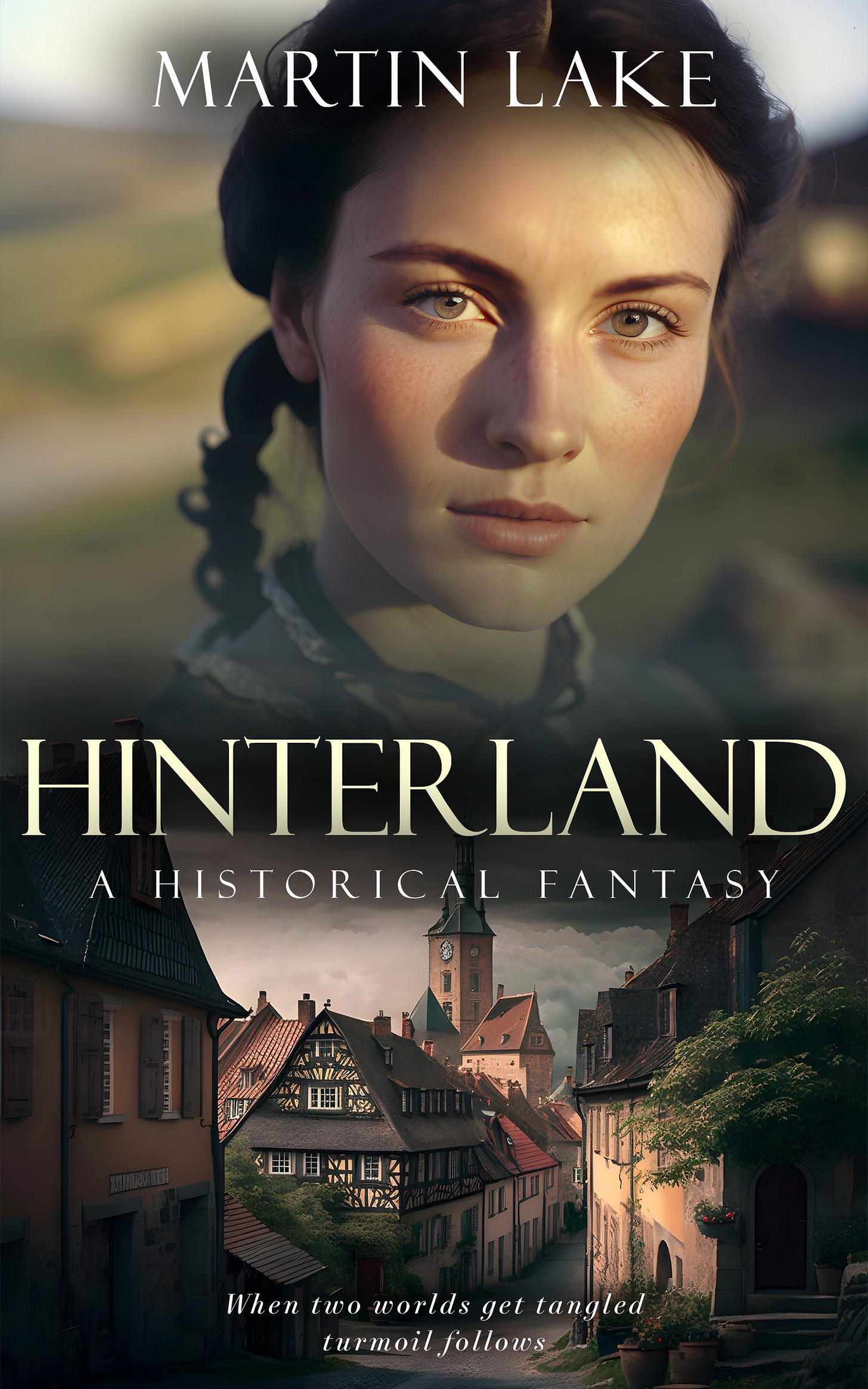

The last thing I need to do is make sure that my chapter headings are all correct and add a list of characters. Tedious for me but helpful for the reader. And then, probably on Sunday or Monday, I’ll publish it on Amazon.

I hope you buy it and share the news with your friends. One of my good friends, who has spent his life in the arts, hadn’t thought of doing this. Word of mouth is the best publicity for a young author like me. (Oops my Pinnochio nose has extended from my face.)

And please write a review and tell the world what you think of it.

Here’s the opening of the novel.

NEWCOMERS

January 1872

Robin Japes picked a handful of snowdrops and placed them in the basket beside a bunch of forced rhubarb. He sniffed the fruit happily. A goodly haul. A rabbit hopped up to him and he bade it good morning.

The rabbit sat back on its haunches. ‘What’s good about it, Robin? A fox has just chased me across the Cathedral Green. Can’t you do something about it? Turn him into a patch of clover so I can eat him?’

Robin shook his head. ‘I don’t meddle in such situations. You’ll just have to run faster.’

He turned at the sound of hooves as a Hackney Coach squeezed through the arch leading from St Andrew’s Street and slowed to a halt directly in front of him. The driver jumped down and opened the door. ‘Here we are sir,’ he said, ‘Choirmaster’s House, Vicars’ Close.’ He trudged up the path with their cases, one in each hand and another tucked under his arm.

A man with rather worn clothes climbed out and gazed at the house. Robin stared at him in surprise, they were a similar height and stature and both of stocky build. If it weren’t for the fact that the man had straw coloured hair while Robin’s was brown, they might have been taken for brothers.

The man helped his wife alight from the cab, took her arm and beamed. ‘Our new home, Emily.’

She pointed at the path. ‘It’s like a forest track, Clarence. All those leaves will be slippery.’ She sighed, hitched up her skirt and opened the gate. ‘Come along children.’

‘They have a family,’ Robin murmured.

He’d no sooner said this than he heard a squeal of excitement from the coach. Three girls hopped from the carriage and scampered after their parents. They were as noisy as starlings, chattering with excitement at the sight of their new home.

‘Hush, girls,’ their father said, glancing around in case anyone was watching. ‘Don’t forget that your papa is the choirmaster of the cathedral. It’s a very important position and you must make a good impression.’

‘They’re excited, Clarence,’ his wife said. ‘It’s understandable.’

Clarence gave a sigh but caught himself doing so and beamed at his family. ‘Come on everyone,’ he cried, ‘let’s see what the house looks like.’

The house was larger than many in the close, with two windows to the right of the door and one to the left. All very normal, except next to it was something rather more peculiar. It was half a house but had a bricked-up door and window on the ground floor. It looked like a face, blank yet at the same time watchful.

The girls ran up the path giggling with delight. Their younger brother Bertie hurried after them but he was not confident on his feet and fell headfirst on the ground.

Clarence gave him a disappointed look, fearing that history would repeat itself. Like Bertie, he had been the only boy in the family and had been thoroughly spoilt. As a man he had come to think such indulgence was a disaster, making him placid and lacking in ambition. He was determined to make sure that the same didn’t happen to his son.

‘Get up boy,’ he told him.

Bertie tried to obey but the leaves were too slippery and he held out his hands to his father for help. Clarence ignored him, walked past and headed to the door. After a moment Robin strolled over and silently helped the child to his feet, brushing the leaves from his hair.

‘Well done, Bertie,’ Emily said. ‘You got up without Papa’s help.’ She followed her husband to the door.

The youngest daughter looked at her mother in surprise. ‘Why didn’t you thank that nice man for helping Bertie up?’

‘Don’t be silly, darling, there was no man.’

But Gracie knew there was. She turned and gave Robin a wave.

Robin stared at the family thoughtfully, particularly at Gracie. ‘Lots of children,’ he said to the rabbit. ‘I’d best go and tell Hazel.’

Clarence opened the door to the house and the family followed him in. A narrow corridor led to the staircase; a tall grandfather clock struck the hour. To the left was an open door.

‘The sitting room,’ Emily said, gesturing the children in. It was dark and gloomy, crammed with oak furniture of a decidedly clerical appearance.

‘Excellent quality,’ Clarence said, running his hands across the back of a chair. ‘Good strong English oak.’

Emily touched it and pulled her hand back. It felt soft, almost as if it were made of treacle. She was alarmed by this, more so when she glanced at her fingers and saw no trace of anything on them.

‘I think it’s a sad room,’ Victoria, the eldest girl said. Her sisters agreed.

‘It will look better when there’s a nice fire,’ their mother said. ‘Come on, let’s explore the rest of the house.’

The next door led into a dining room with an oak table which could seat eight people. There was a large China cabinet, a serving table and a dresser. A French Window overlooked the rear garden. Clarence tried to open it but it was stuck.

‘Probably a good thing,’ Emily said. ‘We don’t want the children to traipse mud in.’

They continued down the corridor to the kitchen. ‘The first kitchen I can call my own,’ Emily whispered to Clarence, happily. In the centre was a large table, with different sized chopping boards stacked upon it and four drawers below. There was a sink and a kitchen range which was large enough to cook meals for the whole family. Copper pans hung above it and an old black kettle sat resplendent on the top.

‘This must be the scullery,’ Victoria said. It was a roomy although dark room with a copper to boil clothes, a large Belfast Sink and clothes horse. Hanging on the wall was a battered old tin bath.

‘Can we go in the garden, Mama?’ the children chorused.

‘Yes. But don’t get muddy.’

It was a small garden, about twenty feet by thirty, laid to lawn and enclosed by high walls with neglected flower beds beneath an apple tree at the far end. A glass frame contained rhubarb although most of the plants had been dug up, presumably by the previous tenants.

‘Can we see the bedrooms?’ Victoria asked.

They squealed in delight and ran back in, racing up the stairs.

‘You must allocate the rooms,’ Clarence told his wife as they followed. ‘I think that Albert will need one of his own.’

‘Of course.’ She touched him gently on the hand. ‘I do wish you’d go back to calling him Bertie,’ she said.

‘I have a position to keep up now, my dear. The name Albert fits better with this.’

There were four bedrooms and Emily speedily chose who would go where. The room overlooking the street faced north; this would be theirs. The other rooms were sunnier which she thought better for the children. Victoria was to have the room next to theirs, then a smaller one for Clarabelle and Gracie and a tiny box room which would just fit in a bed for Bertie.

‘What’s this door for?’ Clarabelle asked.

‘We don’t know,’ Clarence said with a chuckle. ‘Why don’t you take a look?’

She opened the door to find a short flight of stairs.

‘Perhaps it goes to heaven,’ Gracie said.

Her sisters tutted at her silliness. At the top they found a small attic room with timber beams criss-crossing the ceiling. There was a narrow bed, next to it a cabinet with a bible on the top and a small chest of drawers. The window was covered with a sprinkle of ice.

‘I’d like to sleep here,’ Victoria said, hugging herself with pleasure. ‘Can I Papa?’

He shook his head. ‘This will be the maid’s room.’

The girls gave a dubious look. ‘Must we have a maid?’ Victoria asked. They had spent all their lives in their grandparents’ large vicarage and they hadn’t liked the servants one little bit.

‘We need a maid, it’s expected of me with my new job,’ Clarence said. ‘We’ll make sure she’s a nice one.’

Robin pricked up his ears and stepped in front of him, gazing into his eyes. Yes, this one’s susceptible, he thought with pleasure

.

I do so like the sound of this, Martin. Good luck and shall spread the word on social media when you have the universal links ready.