THE ROOTS OF MY WRITING

As I mentioned in my last article, I think that childhood has been a great source of inspiration for me. One of the aspects of childhood which has been most important, of course, is what I read.

I was not one of those precocious children who read Shakespeare and Dickens by torchlight under the blankets. And the teachers at the first schools I went to seemed to think that reading books was not an activity suitable for the classroom. At least not until when I was ten years old and in the stern Mr Allinson’s class. I don’t recall him reading a class book but he did allow us to select books from his bookcase – the school did not have a library. It was here that I discovered Norse Myths and my first science fiction books, the Maurice Grey series by the astronomer Patrick Moore.

But most of my reading was done at home. I was a sickly child, having recurrent bouts of bronchitis so I had plenty of opportunity for it. My dad bought the part-work Knowledge Encyclopaedia which became my premier teacher. I read most of its articles, especially those about history.

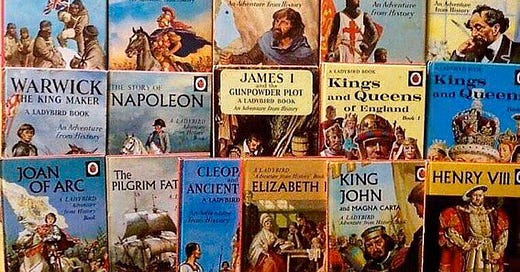

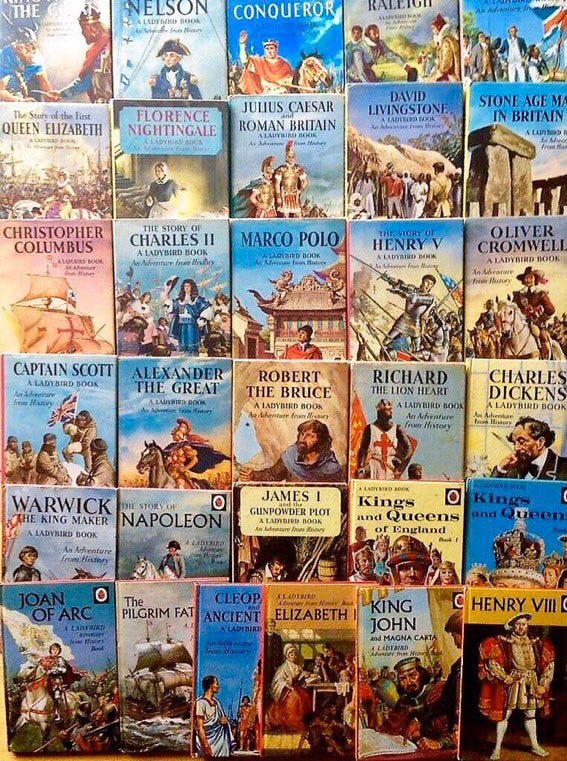

As well as this, some of my favourite books were the Adventure from History Series of Ladybird Books which were illustrated by John Kenney.

I owned most of the books in the picture above and particularly enjoyed Alexander the Great, Joan of Arc, Marco Polo, Julius Caesar and Robert the Bruce. But it was this one which gripped me the most.

Look at Guthrum the Viking’s winged helmet. It would make Thor the Thunder god envious.

I fell under the spell of King Alfred – I’m almost embarrassed that one of the reasons I took a job in Somerset was because I could live close to his hidden refuge of Athelney. I don’t know why Alfred lit the spark more than the many other characters in the series but he did. I suspect I was beguiled by the fact that he suffered such extreme failure and rose above it.

I started my first historical novel about Alfred on Athelney but it got even more lost than he was and I have no idea where the typewritten sheets are now. But my eighth historical novel was about him.

And here is when he first appears in my fiction at the home of the peasant family of Brand, Hild, Ulf and Inga on Athelney island.

The neighing of the horses was louder now and Ulf could hear the sound of their hooves pounding along the timber path which led from Lyng.

And then they appeared. Twenty men, fully armed on powerful steeds. Two men rode at the front, one in a scarlet cloak of finest weave, the other in a tattered grey cloak spattered with mud. The horsemen careered to a halt and the two leaders slid from their horses and looked around.

The eyes of the man in the filthy cloak darted everywhere: taking in the island, the hut, Cenred’s warriors waiting in line, the watery and marshy land around them and the men posted on Barrow Mump to the east. He brushed his hands through his hair and nodded. The man by his side turned to their followers and ordered them to dismount.

He must be a rich lord, Ulf thought, staring at his costly garments. Beneath his cloak he wore a mail-shirt with no tunic to cover it. A long sword hung from a thick leather belt which was studded with gem-stones. A rich lord indeed.

The other man looked ill-favoured in comparison. He flung back his cloak but he wore no mail-shirt beneath, only a mud-stained padded tunic in forest green. On his belt hung a small sword in a stained scabbard and a hunting knife. His leggings were tattered and torn as if had spent weeks running through briers and thick thorns. He looks more like a peasant than a warrior, Ulf thought. But he was riding at the head of the column so he must be important. Perhaps he’s the rich lord’s companion.

‘Is there any sign of the Danes?’ the man asked Cenred.

‘None, my lord,’ Cenred answered. ‘The surrounding land seems deserted.’

Ulf frowned. Can this man be a lord as well? Surely he’s too drab and poor?

‘Does anybody live here?’ the man continued. His voice had an authority which his appearance lacked. ‘In that hut, perhaps?’

Cenred nodded towards Brand and his family.

‘Just these five.’

The man gave them a brief glance and then turned to Cenred.

‘I shall need their hut. Give them a tent for shelter.’

Cenred nodded.

‘What about food?’ the man asked.

‘These people have very little,’ Cenred said. ‘We took hay for our horses but did not touch much of their store.’

‘Then we must hunt and fish and forage,’ said the man. ‘Perhaps the peasant can help. He must know the lay of the land.’

Cenred turned and gestured Brand to approach closer. The family drifted after him, reluctant to let him go closer on his own. Ulf hurried to walk by his father’s side.

The man in the scarlet cloak stared at them as they approached. He looked shrewd and thoughtful. The sort of man who made swift judgements and was rarely mistaken in them. He examined them closely, especially Brand, peering closely at the cuts and bruises on his face. And as he looked at the two women he frowned.

The man in the threadbare clothes paid no attention to the family. It was as if his mind had now moved far away. By his form and figure he looked to be about thirty years of age. But his face looked older, worn and weary as if the troubles of the world were hanging from his shoulders. He had hair as yellow as summer corn but his eyes were dark as hazelnuts.

‘My lord,’ said Cenred. ‘The peasant and his family.’

The man stirred as if waking from a dream and looked at Brand.

‘You live here?’ he asked in a mild tone. He seemed not to notice his battered face.

‘I do,’ Brand said. ‘This is my land. These men are scum and deserve to die.’

Hild reached for Brand’s arm to try to calm him but he shrugged her off. The man’s mild look had been replaced by one of surprise which looked ready to turn to anger.

‘You have no right to be here,’ Brand said, stepping closer and staring into the man’s eyes.

‘He has every right to be here,’ said the man in the scarlet cloak. ‘This is Alfred, King of Wessex.’

Ulf blinked in astonishment.

Brand turned towards the warrior and then back to the poorly-dressed man. ‘The King?’ he mumbled.

Alfred nodded. ‘For the moment, at any rate.’

Hild knelt on the ground and gestured to the children to do the same. Brand remained on his feet although he took a couple of steps back from the king. His surprise was disappearing and anger was taking its place.

‘You say you are the King?’ he said. ‘And yet you allow your men to behave as they did to my wife and child. They are worse than heathen savages.’

Alfred looked perplexed. ‘What do you mean?’ he asked.

‘They raped them,’ Brand cried. ‘Your brave, grand warriors raped my wife and daughter. Raped my wife and child while the rest of them were waiting their turn, baying like hounds, slavering like beasts.’

Inga began to sob at his words, the memory of her ordeal hurtling back to the forefront of her mind. Ulf hugged her tightly but turned to look at the King to see how he would react.

Alfred shook his head as if confused or perhaps unable even to comprehend what Brand was saying. Then he pursed his lips and stared at Brand.

‘I have no time for this now,’ he said. ‘I must give thought to weightier matters.’

He strode off down the hill, his eyes now focused to the north. The man in the scarlet cloak put his hand on Brand’s shoulder. ‘We will talk of this later. I am Edgwulf, the King’s Horse-thegn. I shall hear what you have to say later on. But do not burden the king with this story again.’

He turned and hurried after the king, standing beside him and gazing to the north.

A mere ten miles away the triumphant Viking army had set up camp and was preparing to hunt for them.