I’ve just had a week in Somerset seeing old and very dear friends. The second part I spent in Taunton and visited Sherbourne which was glorious and Lyme Regis which was wet and cold and misty but still lovely. I never fail to think of the French Lieutenant’s Woman when I go there and I’m going to buy it.

The first four days, however, I spent in Wells helping celebrate my oldest friend’s wedding anniversary and joint birthday with his wife. Wells is the smallest city in England, with a wealth of higgledy-piggledy housing and streets which actually run with water from ancient wells.

It is dominated by an ancient cathedral which is splendid. I made a typo just now, calling it a castle, and in many ways it was. I wrote last week about the barriers between rich and poor in England (and of course, the rest of the world) and the disparity between the two is displayed in Wells in mighty measure. The cathedral is larger than most castles, more imposing and lovelier by far.

Like every great building around the world the cathedral would have been built by people who lived in tiny little houses, probably little more than shacks. Perhaps the glorious edifice was surrounded by a shanty town of itinerant workers who lived and died in squalor while they raised this miracle of stone. I wonder if many resented the fact.

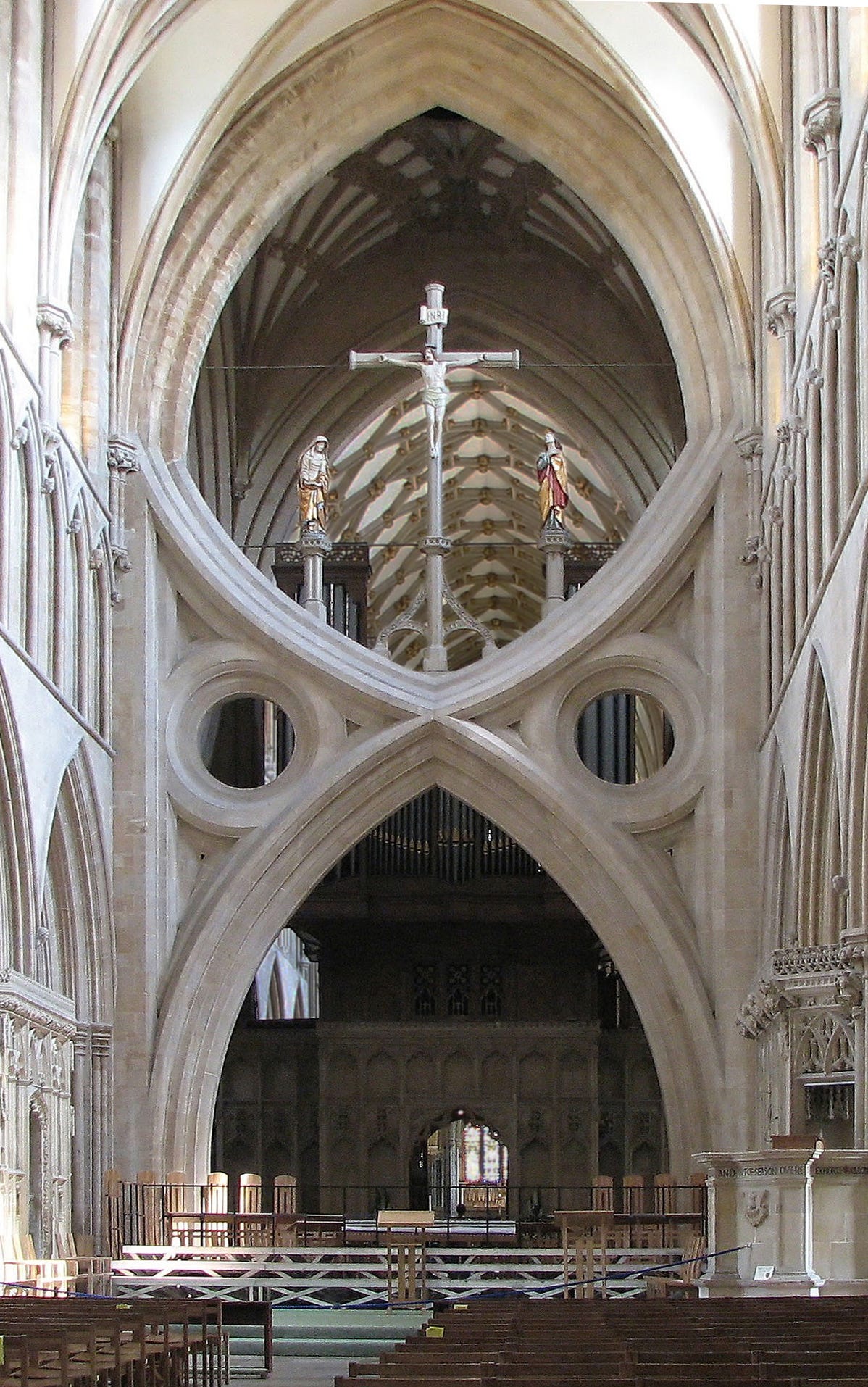

The sheer technical mastery needed to build such a vast place is unbelievable. The mathematics involved must have been mind-boggling, often with the masons learning lessons along the way. One of the most astonishing parts of the cathedral is the scissor arch inside. It’s functional, it works and above all it is sublimely beautiful.

Image courtesy of Adrian Pingstone.

And so are the statues, carvings and decorations. One of the more fascinating things for me is the amount of work that went into them and yet many are so dizzyingly high no one can see them closely enough to appreciate their shapeliness and splendour. Perhaps the sculptors designed them only for the eyes of angels.

The cathedral was not only a place of worship and beauty, it was a place of power. The cathedral was the seat of the bishop of Bath and Wells which was one of the least wealthy in the country. Nevertheless, the bishop lived in a splendid palace. The cathedral owned much of the town and surrounding countryside and many, perhaps the majority of the townsfolk worked for it or were in some ways economically dependent on it.

I’ll say more in a future post about the street where I’m going to set my new novel. But I’ll finish with this anecdote.

The antagonist of my novel is Jacob Mews, the Canon Precentor of the cathedral, the most important official other than the Bishop and Dean. One of his key complaints and driving factors is that he was not allowed to live in his allocated apartment. His predecessor is so old and frail, the Dean does not think it fair to move him out for the few months remaining to him. So Canon Mews is required to live in one of the houses of Vicars Close.

It seemed very reasonable an idea to me. Until I wandered around Wells.

I came upon the site of the old Deanery. The high walls meant you could not see inside and it had a sturdy wooden door. I assumed it would be locked but, to my surprise, found that it was not so I went into the inner courtyard. I was astonished. The Dean lived in something akin to an aristocrat’s country house. So, I reasoned, a Canon Precentor, the next below in the hierarchy, would not be allocated an apartment and would certainly never be allowed to live somewhere as mean and cramped as one of the houses in Vicars Close.

One of the guides on an excellent tour told us that the Canon actually lived in a marvellous and very large building adjacent to the Dean.

Finding this out requires me to change a great deal of the opening chapters and to decide on a different reason for the miserable temperament of the canon.